LOSING his dad as a teen was “truly horrible” for JC Clapham but the father-of-three was soon faced with his own moment of despair.

IT WAS Saturday, March 28, 1998, when I received the news that would cast a shadow over the rest of my life.

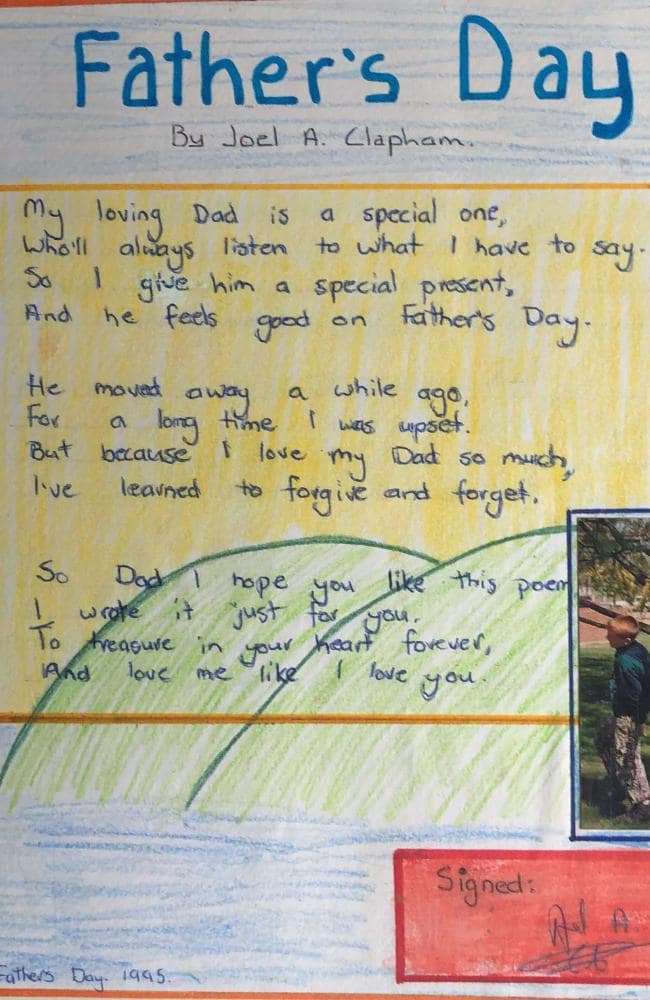

I was 16 years old, and nothing would ever be ‘normal’ as I knew it, again. My dad had killed himself and now, 20 years on, I still have a father-shaped hole in my heart that won’t ever be filled.

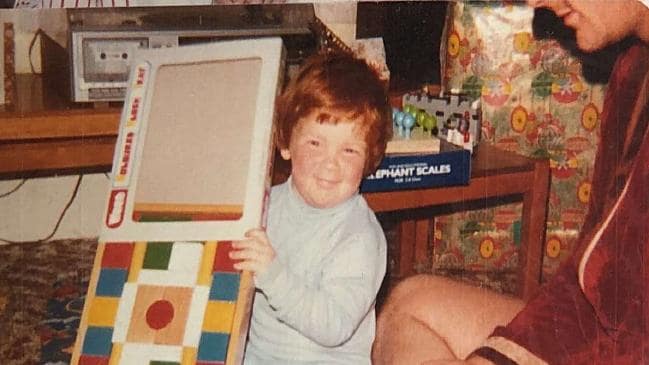

My parents had split up five years earlier. More truthfully, my father had walked out on us — my mum, my two younger brothers and me — the day before my 11th birthday. It would be the first of many I would spend without him.

We saw dad on school holidays. Most times we spent a week with him, and most summers it was two weeks.

But in the summer of 1997/98, I’d turned 16 and my brothers and I spent three full weeks with our dad — it was the longest stretch of time since he moved away.

That summer, dad and I connected as two people: it felt at the time like we were becoming more than just father and son — we were becoming friends.

Dad promised to buy me an old car for my 16th/17th/18th birthday presents and said we’d do it up together during school holidays. He was a car man and said I could have any type of older car I wanted. The choice was mine … so long as it was a V8 Holden Premier. What a choice! I was happy regardless, as it would kind-of be ‘our’ car.

My dad and I had our first beer together and our second cigarette … our first shared smoke was when I was seven and asked for one out of curiosity and dad obliged (1988 was a very different time!).

I talked with dad about my idea of moving in with him after I finished high school, and my plan to go to uni in Warrnambool and help with his fourth son, my much-younger brother, who’d be school age by then. Father-and-son taking on the world with our restored car. I couldn’t wait!

All my life my father was my idol, my hero, despite him being moody and absent a lot, even before he moved away. Dad was big and strong at 6 foot 3, and as solid as a brick s***house. He was a tough footy player and often kicked bags of goals, got into a fight on the field (he usually won), and even took a grand final-saving speccy one year, which I had on video and watched a lot.

In contrast with the tough guy others mostly saw him

So in 1998, to be connecting with my dad as a friend and planning a future with him, was a special dream that was starting to come true.

But … none of the things my dad and I planned actually happened. Not one of them. Because eight weeks after that summer together, just as we’d started to become the friends that I had long wished for us to be, my dad wrote a note of goodbye, walked into his garage, and took his own life.

My dad left me. Again. And permanently. Why would a father choose to leave his kids forever? My love for him became clouded by hatred for what he’d done.

I’ve wondered since on so many occasions, why he didn’t just pack up and take off to the middle of nowhere for however long he needed a break for. Why not just disappear until he felt good again?

But he didn’t. He opted out of my life in the most permanent and irreversible way.

In the 20 years since dad killed himself, I too have faced some significant challenges. Whether it’s from genetics or trauma from aspects of my childhood, I’m not sure, but mental ill-health has come quite savagely for me, too.

My first major dark period climaxed when I was 22. I was drinking a lot at that time and not dealing with things well. After one too many setbacks (and far too many drinks on this particular night), I was in more pain than I felt I could handle.

I walked out of the pub and jumped off a bridge. I landed on the road about seven metres below, and largely because of how drunk and limp I was, I survived with only a broken pelvis and wrist.

Three months of bed rest, physical therapy and psychological rehabilitation followed. During those long and very bleak months I came to see just how pained my dad must have been at the end, and how helpless he must have felt. I had nearly joined him, but a tiny flicker inside me hadn’t gone out, and I soldiered on.

‘I FELL APART COMPLETELY’

I became a father 10 years ago and it was the most amazing feeling to say the very least. Father’s Day would be a happy day for me again, after a decade of crying on the first Sunday of September every year — looking at the sky and cursing my dad.

My son Leo was later joined by his brother Gus and sister Ada. I have three great kids who are all happy, healthy, and smart, and I’m so proud of them.

But as it so often happens for those who have battled the Black Dog, I’ve again been visited by mental ill-health, even though my life — on paper — was pretty good. This last dark period for me culminated in having a total breakdown just as my marriage to my kids’ mother ended a couple of years ago.

Before my marriage ended, the writing was on the wall for a few years. My then-wife and I had grown too far apart and weren’t able to bridge that significant divide.

A couple of weeks after my now ex-wife and I both agreed we should separate, my GP forced me to take a month off work so I could focus solely on surviving — it really was that fraught.

I found a place to live, moved out, and fell apart completely. I was told to take another month off work, then another, and eventually I resigned from my promising corporate career and found my entire life changing all at once. And every day since, without exception, the possibility of suicide has popped into my mind as a possible way to wipe away the hurt and sadness and tears and despair that have nearly drowned me.

But the upside of losing my father to suicide means I know what it’s like to be the child left behind. And it’s really, truly, horrible.

THE SILENCE THAT KILLED MY DAD

My dad didn’t ask for any help. He didn’t talk to anyone about how bleak things seemed, let alone see a professional for medical help. And that silence meant he died.

I want the opposite outcome for my kids, and for me as a father. So in order to achieve the opposite outcome to my dad, I also take the opposite steps to him: I talk to people, I seek and accept medical help, and I don’t much care what other people think of me being so candid.

I am very open about my challenges with my mental health. I am now very open about my suicide attempt 15 years ago.

It’s my love of storytelling that led to me sharing the story of my dad as a one-person ‘compassionate comedy’ show, Humpty Dumpty Daddy. At fringe and comedy festivals around the country, I have stood on stage and poured my heart out to audiences for an hour at a time, sharing everything I have in this article, plus more.

The reaction from audiences has largely been quite heart-warming. After I walk off stage, I wait at the exit and thank people for coming along. And every single time, I have seen one or more burly men with quivering faces, or open arms for a big man-hug, or a pair of eyes that bore into mine with a declaration of camaraderie and shared trials.

Women are more verbally open about what they think and the raw warmth and honesty they say they feel from seeing one of my shows. My audiences seem to be 2:1 women to men, but it’s the men who have stronger and more impactful emotional responses. Quite a few have contacted me later on and shared their own story, and some have become people I still correspond with. It’s incredibly special, and I’m so grateful that by being vulnerable and open, I feel connected to more people than I ever have.

I know now it’s not my fault, but I wasn’t enough to keep my dad alive. He lost all hope completely, and of course I wish I could have done something to stop him. But I couldn’t. I have the benefit of living in a more understanding time than my dad, though there is a long, long way to go, as the 10 per cent increase of suicides from 2016 to 2017 attests.

And while it’s taken me nearly 20 years to recognise, I can now see that the greatest lesson my father ever taught me was what NOT to do.

My dad felt a failure at life and succeeded in dying. I failed at dying but am beginning to feel a success at life. Not a bad change in one generation.

JC Clapham used to wear a suit to work every day. He is now retraining as a mental health worker, does storytelling shows and writes about mental health and masculinity.

If you or someone you know needs support with their mental health, please contact one of these support

• Lifeline 24/7: 13 11 14 or www.lifeline.org.au

• Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467 or www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au

• MensLine Australia: 1300 78 99 78 or www.mensline.org.au

Originally published 13/10/2018 at news.com.au